Creating Safe Cities & Sexualized Violence in the Age of COVID-19

Vancouver Reopens & Sexual Assaults by Strangers Rise

July 1st saw the long awaited return of Vancouver’s nightlife after months of closures and restrictions. As BC moved into Step 3 of it’s Restart Plan the hospitality industry rejoiced having struggled to stay afloat through the pandemic. The reopening signals a return to another normal – one of unaddressed, rampant stranger-based assaults in Vancouver’s nightlife.

Vancouver’s Granville Strip at Night (Photo Credit: Will Young, ThinkPol.ca)

BWSS Takes to The Streets! Safety Changes Everything.

In the last year, BWSS saw a growing number of women and girls in need of street-based interventions and resources and in May of this year launched their street-based Outreach Program ‘Safety Changes Everything’. The goal of the Safety Changes Everything Team is to be a visible presence within communities. Building relationships with women and girls to community-based resources, as well, and providing immediate crisis-interventions.

Responding to the to growing numbers of street-based, stranger-based assaults on the Granville Strip , BWSS teams are increasing their presence amongst Vancouver’s nightlife. The Safety Changes Everything Team, wants people to know if they are in distress and experiencing sexualized-violence or abuse to reach out. The Safety Changes Everything Team is available to provide immediate crisis response, emotional support, connect people to resources, advocacy and accompaniment to police, the hospital or medical services.

BWSS has been calling for action by the City of Vancouver, particularly in the Downtown Eastside and Granville Entertainment District since early this year. Confirming what the Safety Changes Everything Team had been reporting, last week VPD released new figures which show a 129% increase in reported cases in the month of July alone – prompting them to relaunch the Hands Off! campaign.

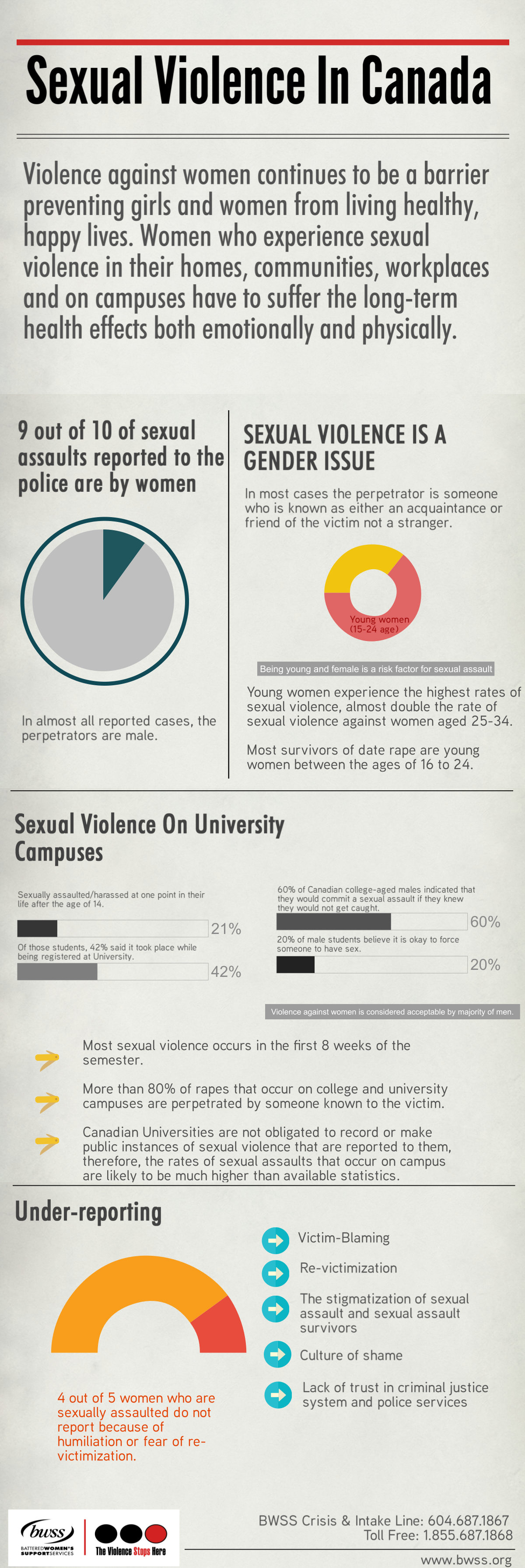

Rarely though are sexual assaults reported to the police.

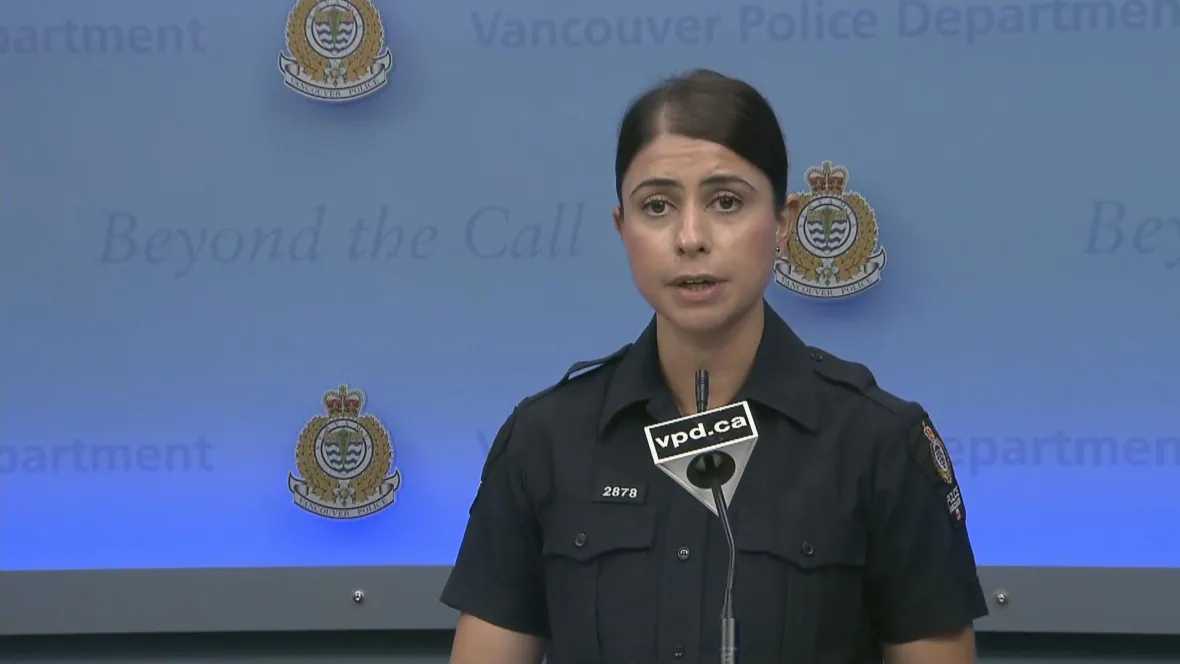

Vancouver police Const. Tania Visintin says even with the recent increase in reports, sexual assaults are vastly underreported. (CBC News)

City of Vancouver and the UN Safe City Initiative

Vancouver is one of six Canadian cities which is part of the UN Safe Cities and Public Spaces Initiative – a global initiative led by UN Women. The initiative aims to address gender-based and sexualized violence and harassment by focusing on the City’s policies, planning, programs and services and how they can be changed and applied to increase safety and build safer public spaces.

Vancouver is one of six Canadian cities which is part of the UN Safe Cities and Public Spaces Initiative – a global initiative led by UN Women. The initiative aims to address gender-based and sexualized violence and harassment by focusing on the City’s policies, planning, programs and services and how they can be changed and applied to increase safety and build safer public spaces.

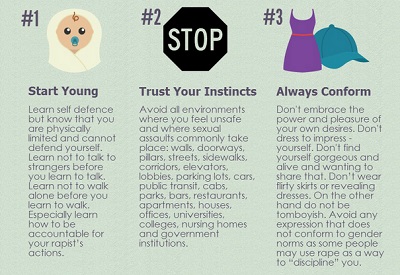

BWSS knows that gender-based, sexualized violence and physical expressions of violence are systemic issues. We know that prevalent normalization of violence and attitudes and beliefs rooted in racism, colonialism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia and ableism express themselves in ways that harmful and often deadly – particularly for Black, Indigenous, immigrant Women of Colour and 2SLGBTQQIA+ communities.

BWSS has been on the frontlines of work to create safe public spaces for decades – working in partnership with TransLink, bars & night clubs, and through our street-based community outreach team. As advocates for women and children experiencing gender-based, sexualized violence and harassment we routinely bring forward recommendations at all levels of government on policy and legislation which directly impacts Women’s safety in public spaces.

The City of Vancouver is now in the first phase, scoping study of the initiative. This involves a survey to gain a deeper understanding of gender-based violence and sexualized violence and harassment in public spaces.

The survey is open to anyone who has experienced or witnessed gender-based and sexualized violence or harassment in Vancouver. Examples include unwanted touching, cat-calling, being followed, or homophobic, transphobic, and racist harassment.

The survey is available in English, Mandarin, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Punjabi and Spanish

Some of the questions on the survey could bring back or remind you of upsetting or traumatic memories and trigger uncomfortable to intense emotions, sensations or other responses. If you are feeling triggered during the survey, feel free to stop at any point or take a break and come back to it.

BWSS is available through our 24-hour Crisis Line by phone 604-687-1867 for those requiring support and resources.

More details on this The City of Vancouver’s Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces Initiative can be found at https://vancouver.ca/people-programs/un-safe-cities-and-safe-public-spaces-initiative.aspx