Sep 16, 2025 | Battered Women's Support Services

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

September 16, 2025

Three Women Killed, One Man Charged

Anti Violence Organization Responds to Yet More Vancouver Killings with Five Urgent Actions to Prevent the Next Femicide

Vancouver, BC: This week, three women are dead in East Vancouver, two were killed at the scene and a third died later in hospital from injuries inflicted by the same man. Charges have now been laid. This is the third known death connected to one individual, and it is also the latest in a devastating pattern of gender-based killings in British Columbia.

Battered Women’s Support Services has tracked thirty-five women and girls killed in this province over the past thirteen months. This is the highest number recorded in such a short period in recent memory and yet, there has been no co-ordinated response. There are no emergency measures, there have been no signal from anyone that these deaths are being treated as preventable. At the moment, there is no official data on these killings tracking these deaths.

These are the essential questions: Did the man who killed them know them? Was there a past relationship between the victim and the accused? Were there identified known risks that could have pointed to opportunities for intervention?

“We have asked the Vancouver Police Department to publicly disclose whether the man now charged had a known intimate relationship with one or more of the women.” Said Angela Marie MacDougall, Executive Director, Battered Women’s Support Services. “The public deserves to know whether any system had prior contact, and whether any intervention was possible before these women were killed. This is in the public interest.”

The majority of women who are killed in this province are not killed by strangers. Rather they are killed by men they know, and many are killed by former or current intimate partners, while others are killed by acquaintances, neighbours, family members. ime and time and again, there are signs and patterns, there is history, there is escalation and often there are systems that failed.

“These failures are not abstract, they are structural.” Said Summer Rain, Manager of the Justice Centre at BWSS, “They include the absence of consistent, mandatory risk assessment and they include the chronic underfunding of the very services women turn to for protection. They include the silencing of survivor knowledge, the erasure of community-based prevention, and the lack of urgency in the face of death.”

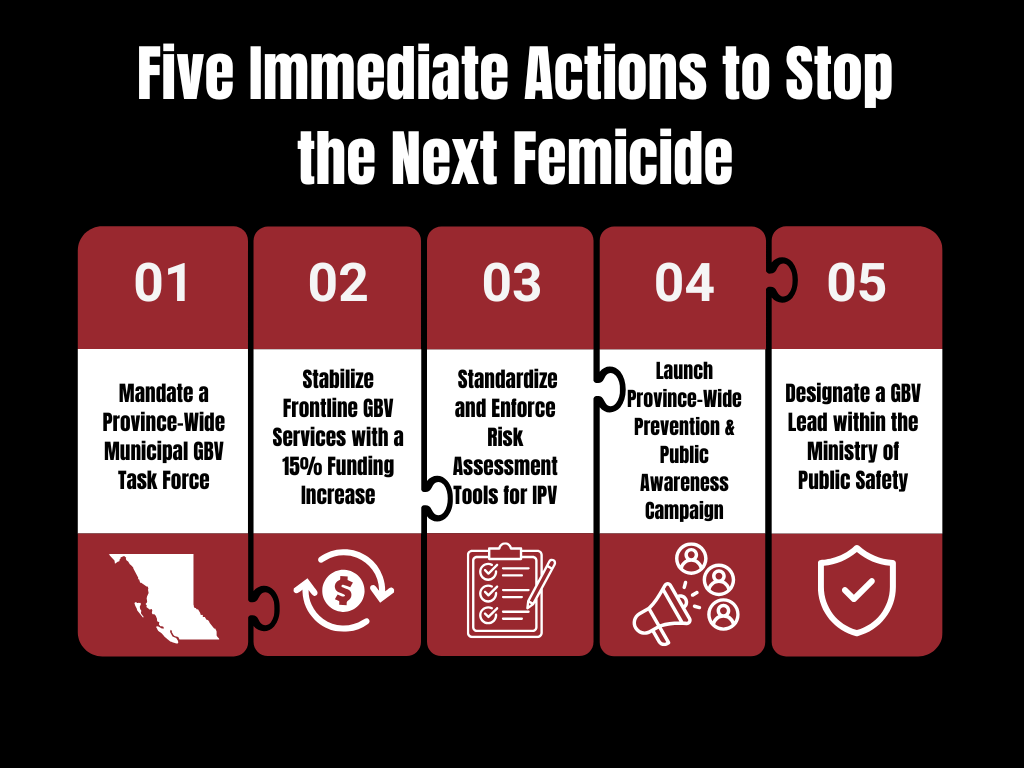

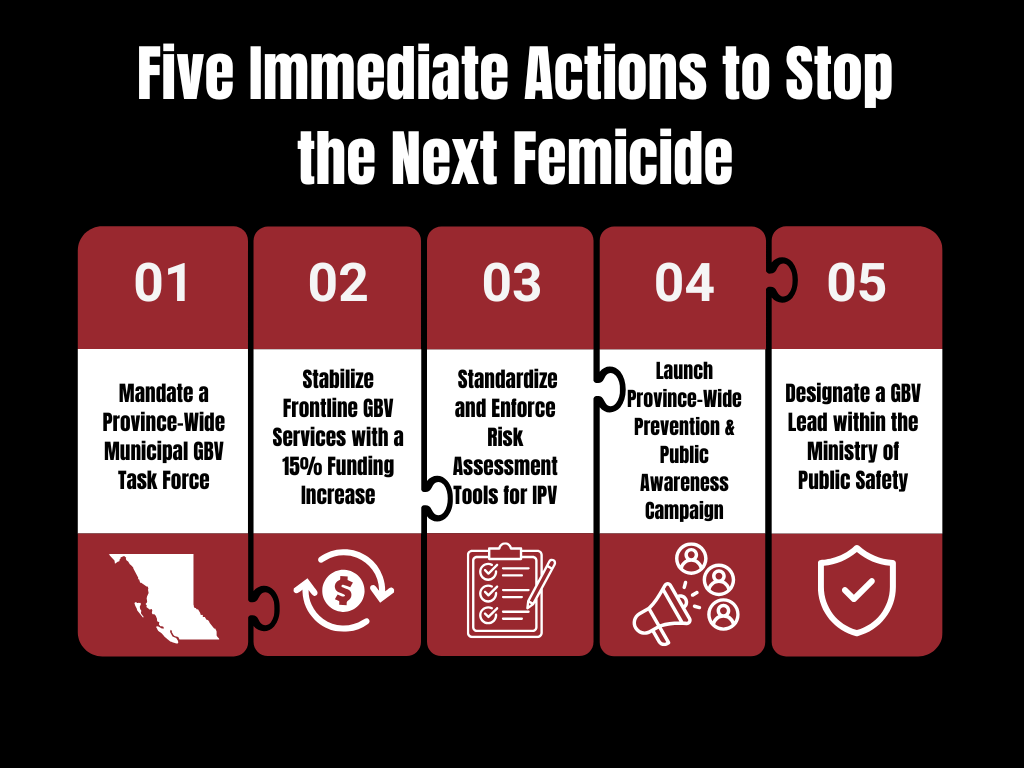

The crisis has already been named, and it does not need to be named again, instead action needs to be taken to interrupt it. BWSS has outlined five emergency actions for the Province of British Columbia to take without delay. They are requiring municipalities to establish a gender-based violence task forces, developed in partnership with Indigenous leaders, survivors, and community organizations, to immediately stabilize the frontline funding essential services women rely on when at risk: crisis lines, transition houses, victim services, legal advocacy, and trauma and violence-informed counselling. The province must implement a standardized, mandatory risk assessment framework for intimate partner violence and femicide across all public systems, including policing, health, justice, family law, and child protection.

Importantly, the province must launch a long-term, province-wide prevention & education campaign to help shift this problematic social problem, to help people recognize early warning signs, support those at risk, and shift the burden of change to those who cause harm.

Finally, the province must establish a lead for gender-based violence within the Ministry of Public Safety and Attorney General offices to ensure a co-ordinated and accountable response across ministries and systems.

With these five actions, there are evidence-based, specific, immediate, necessary interventions that will save lives.

“Every femicide that is not prevented is a policy failure and staying silent after a killing is a choice.” Said Angela Marie MacDougall. “What matters now is not how we name this crisis but whether we act.”

“We are well past the time for declarations and grandstanding” Said Angela Marie MacDougall, Executive Director at BWSS. “Declaring gender-based violence an epidemic is not an action; it is words that will not stop a man from killing his partner. It will not identify the risk he poses to the next woman. It will not fund the shelter that turns her away. It will not hold police and legal systems accountable who dismiss this violence. And…it will not bring back the women we have already lost.”

About Battered Women’s Support Services (BWSS)

Battered Women’s Support Services takes action on violence against women and gender-based violence through direct services, legal advocacy, education and training, and law reform. Based in Metro Vancouver, BWSS works to transform systems and advance social and structural change to ensure safety, justice, and equity for women, girls, and gender-diverse people.

Sep 10, 2025 | Battered Women's Support Services

In the past 13 months, 34 women have been killed in British Columbia. Each was loved, cherished, and irreplaceable. Each should still be alive today.

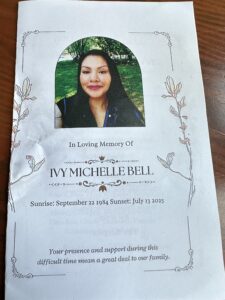

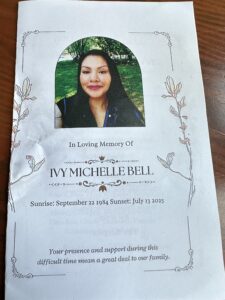

Last week, we gathered in Gastown at the vigil for Ivy Michelle Bell. This weekend, we stood with family and community in Maple Ridge to honour Jessica Cunningham. This Saturday, we will travel to Kelowna for the celebration of life for Bailey McCourt.

These gatherings are moments of profound grief. They are also reminders of love—the love families and communities hold for women whose lives have been stolen by male violence, and the love that fuels our fight for change.

What’s at Stake

Just this past Friday, Vancouver police confirmed two women were killed and one seriously injured. A man has since been charged with second-degree murder and aggravated assault.

This horrific event is part of a devastating pattern. In BC, femicide is not an isolated act. It is a public safety emergency.

What We’re Doing Together

At BWSS, we are pressing forward with urgency on five immediate interventions designed to end femicide in BC—five actions that are clear and achievable:

-

Mandate Municipal GBV Task Forces – Every city must take action, convening survivor-centred task forces to coordinate safety across policing, housing, and justice.

-

Stabilize Frontline Services – Provide a 15% emergency funding increase so community-based victim services, STV outreach, and transition house workers can meet demand.

-

Standardize Risk Assessment – Make intimate partner violence risk tools mandatory across police, Crown, child protection, and more, with oversight and enforcement.

-

Launch a Province-Wide Prevention Campaign – Use government communications infrastructure to educate the public and prevent violence.

-

Appoint a GBV Lead – Establish a provincial lead in Public Safety/Attorney General’s office to coordinate across ministries and municipalities.

Pushing at Every Level

Last month, BWSS convened a provincial roundtable on gender justice and ending violence, bringing together advocates from across BC, including organizations representing Indigenous, Black, rural, and remote communities, to meet with Canada’s Minister for Women and Gender Equality, Rechie Valdez.

The meeting opened with a territorial welcome and a moment of silence for women and girls lost to femicide, setting the tone for deep reflection and shared resolve. Together, participants presented three urgent federal asks:

-

Stable, multiyear core funding for the sector

-

Shifting investments toward the care economy, housing, and prevention

-

Independent, survivor- and Indigenous-led accountability for the National Action Plan on GBV and the MMIWG Calls for Justice

The Minister was invited to carry these priorities forward to Cabinet, and participants affirmed that survivor safety is public safety, committing to reconvene ahead of the Fall 2025 federal budget.

BWSS was joined by powerful voices including Amy FitzGerald (BC Society of Transition Houses), Nataizya Mukwavi (Black Women Connect Vancouver), Sharon Gregson (Coalition of Childcare Advocates of BC), Alice Kendall (Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre), Ninu Kang (Ending Violence Association of BC), Jennifer Mackie (Fraser Region Aboriginal Friendship Centre Association), Sue Brown (Justice for Girls), Lisa Schmidt (‘Ksan Society), Lynnell Halikowski (Prince George Sexual Assault Centre), Shahnaz Rahman (Surrey Women’s Centre), Laurie Hannah (Westcoast Community Resources Society), and Shannon Daub (West Coast LEAF).

We thank these incredible leaders for sharing their voice, brilliance, and presence.

Advocacy in Action

Alongside community partners, BWSS has been meeting with mayors across BC, urging immediate action—and the response has been encouraging.

We continue to work directly with the Attorney General’s office. Attorney General Niki Sharma has shown clear understanding of the urgency and what is at stake, and we are grateful for her leadership.

Just today, BWSS met with the Premier, the Attorney General, Deputy Minister Shannon Salter, and senior staff to reiterate the five immediate interventions. The conversation was effective, and while we are encouraged, we remain determined to keep pushing until change is realized.

Read More

How You Can Help

Our strength comes from survivors and communities standing with us. Thank you for signing on to #DesignedWithSurvivors. Here’s how you can support right now:

We cannot bring back the women we have lost. Together we can build a BC where survivors are safe, women’s lives are protected, justice is upheld, and femicide is no longer tolerated.

Sep 10, 2025 | Battered Women's Support Services

A public safety failure. A systemic pattern. A chance to act. Gender-based Violence is endemic

Since just the end of May, we’ve seen multiple femicides in communities across B.C.—a cascade of loss rooted in gaps at every level of the system. Even when survivors reached out, the responses were fragmented: RCMP failed to respond, risk assessments were missed, legal protections went unenforced, and frontline services remained undervalued.

These aren’t isolated incidents. They’re not crises of compassion. They are the predictable outcomes of systems that were never built with survivors in mind.

This is what a public safety failure looks like.

For too long, public safety has been narrowly defined by law enforcement. But policing alone cannot prevent femicide. True public safety means coordinated action across all levels of government. It means legal systems that protect, social systems that respond, housing systems that shelter, economic systems the support survivors, and health systems that heal. It means trauma- and violence-informed services that meet survivors before crisis hits.

Public safety doesn’t end with the police—it starts with all of us.

We cannot wait for the next tragedy. That’s why BWSS is putting forward Five Immediate Provincial Actions to Stop the Next Femicide—designed to embed survivor-informed safety across public systems.

Five Immediate Provincial Actions

1. Mandate a Province-Wide Municipal GBV Task Force

Establish a cabinet directive requiring every municipality to convene a gender-based violence (GBV) task force. Terms of reference should ensure victim/survivor-centred practice, community-based leadership, and coordination across public safety, housing, and justice systems—starting with intimate partner violence (IPV) as a core priority.

2. Stabilize Frontline GBV Services with a 15% Funding Increase

Provide $14.1M in crisis stabilization funding to address wage disparities and growing demand across PEACE, STV Outreach, and Community-based Victim Services Programs. Priority should be given to services responding to IPV, where staffing shortages are putting lives at risk. This funding can complement ongoing collective bargaining processes and serve as a workforce retention measure.

3. Standardize and Enforce Risk Assessment Tools for Intimate Partner Violence

Mandate consistent use of approved IPV risk assessment tools (e.g., SIPVR) across police, Crown, and MCFD. Introduce enforcement, oversight, and training mechanisms to ensure these tools are not optional but standard public safety protocol.

4. Launch a Province-Wide Prevention and Public Awareness Campaign

Phase in education and prevention programming, beginning with a cross-ministry public awareness campaign on intimate partner violence. Build on existing provincial communications infrastructure (e.g., wildfire, overdose, vaccine messaging). Future phases should include GBV prevention in schools, workplaces, and community settings.

5. Designate a GBV Lead within the Ministry of Public Safety

Appoint an interim or permanent cross-ministerial lead on GBV—ideally with IPV experience—to coordinate implementation, liaise with municipalities, and ensure alignment across justice, housing, and health etc. This role can be assigned via internal realignment, without triggering new hiring or budget allocations.

Our proposal is not aspirational, it’s urgent and actionable. When public safety means more than sirens—and is built with survivors in mind—lives change. A survivor-centred infrastructure saves lives before tragedy strikes, offers healing on the other side of abuse, and dismantles the belief that violence is inevitable.

This is our moment to act. We must transform the system, starting now, and do so with unwavering survivor leadership. If this feels like the public safety you’ve been waiting for, stand with us, please ask your municipality to form a GBV task force, demand risk assessment enforcement, support frontline services, and insist that GBV be treated as the public safety emergency it is. Together, we can stop the next femicide not after it’s written in headlines, but before the violence ever begins.

Sep 8, 2025 | Battered Women's Support Services

From Vigils to Action: Toward Ending Femicide in British Columbia

Last weekend, we attended the vigil for Ivy Michelle Bell. Yesterday, we gathered with family and community to honour Jessica Cunningham. This Saturday, we will travel to Kelowna for the celebration of life for Bailey McCourt.

These gatherings are moments of profound grief. They are also reminders of love — the love that families, friends, and communities hold for women whose lives have been stolen. Each woman was unique, cherished, and irreplaceable. And each should still be alive today.

And just this past Friday, Vancouver police confirmed that two women were killed and one woman seriously injured. A man has since been arrested and charged with second-degree murder and aggravated assault. While details are still emerging, what is already clear is that this case belongs to a devastating pattern: in just 13 months, 34 women have been killed in British Columbia.

A Devastating and Preventable Pattern

Whether inside their homes or in public spaces, women and girls are being killed by men. Some by partners or ex-partners, some by acquaintances, some by strangers. These are not isolated tragedies. They are the visible tip of a crisis that has been normalized, dismissed, and too often explained away as private.

We need to be clear: femicide is preventable. Every one of these women should still be alive. Every community gathering at a vigil this month is mourning not just the loss of one life, but the failure of a society that refuses to take violence against women seriously as a matter of public safety.

What Women and Girls Are Carrying

Each time another headline announces a woman killed or a sexual assault, women and girls across BC feel the weight:

- Fear and Hyper-Vigilance – “It could be me. It could be my daughter. It could be my friend.” Women and girls are reminded again that their daily safety is not guaranteed — on the street, in their homes, at school, at work. They carry an invisible burden of safety planning: checking surroundings, sharing locations, avoiding certain spaces, calculating risks in relationships.

- Anger and Frustration – “Why does this keep happening? Why doesn’t anything change?” Many feel outrage at the normalization of male violence, and at systems (police, courts, governments) that appear reactive at best, negligent at worst. There’s anger at hearing condolences instead of commitments, promises instead of action.

- Grief and Exhaustion – “Another one. Again. I can’t bear to read the details.” For survivors, each new killing or assault can trigger trauma and memories of their own experiences. Even for those not directly affected, there is collective mourning and fatigue — the sense of an endless cycle of loss.

- Solidarity and Connection – “That could have been me — I understand her fear, her pain.” Many women and girls feel immediate empathy and identification with victims and survivors. This can fuel solidarity, mutual care, and collective calls to action — vigils, marches, petitions, demands.

- Distrust and Disillusionment – “The systems meant to protect us are failing.” News of another killing reinforces the sense that police, courts, governments, and community institutions do not prioritize women’s safety. Girls growing up with these headlines may begin to believe that violence is an inevitable part of being female.

- Resolve and Defiance – Alongside grief and fear, many women and girls channel their emotions into resistance: “We will not be silent. We will organize, fight, and protect each other.” Especially among younger generations, repeated tragedies are radicalizing new voices demanding systemic change.

This is the emotional climate that femicide creates. This is the reality that families, survivors, and communities are forced to carry while governments delay.

This is a Public Safety Crisis

If three men were killed on the street in one week, there would be immediate calls for a public inquiry and emergency action. When women are killed again and again — 34 in just over a year — we hear condolences, but not coordinated action.

Violence against women is not an unfortunate private matter. It is a public safety crisis. It belongs in the same category of urgent government response as wildfires, pandemics, and organized crime.

Five Immediate Actions to End Femicide

On July 20th, we presented the Premier with five immediate actions the Province of BC could take today to prevent femicide and save lives. These are not aspirational. They are feasible, affordable, and urgent:

- Mandate Municipal GBV Task Forces – Every city must convene a survivor-centred task force to coordinate safety across policing, housing, and justice.

- Stabilize Frontline Services – Provide a 15% emergency funding increase so crisis lines, outreach, and victim services can meet demand and keep survivors safe.

- Standardize Risk Assessment – Make intimate partner violence risk assessment tools mandatory across police, Crown, and child protection, with oversight and enforcement.

- Launch a Province-Wide Prevention Campaign – Use existing government communications infrastructure to educate the public and prevent intimate partner violence.

- Appoint a GBV Lead in Public Safety – Designate a dedicated provincial lead to coordinate this work across ministries and municipalities.

- These five steps will save lives. The solutions exist. What is missing is political will.

BWSS Advocacy and Municipal Leadership

BWSS has and continues to meet with government officials, ministries, and community organizations across BC to keep pushing for the change needed. We are advancing survivor-centred approaches to public safety, bringing evidence, solutions, and survivor voices to the table.

At the same time, we have begun our own work directly with mayors and councils. From Surrey to Burnaby, from Maple Ridge to Prince George, municipalities are stepping forward to recognize gender-based violence as a public safety crisis. Local governments are creating space for survivor-centred safety planning and demanding provincial leadership.

When municipal leaders say, “This is our responsibility too,” they are modeling the kind of courage the Province must now follow.

Grief, Rage, and Action

We will continue to stand with families at vigils, to bear witness to the lives taken, and to honour the love that communities carry forward. But grief alone is not enough. We will continue to rage at the systemic failures that leave women unprotected.

And we will continue to demand action until the killing stops. Families should not have to gather week after week in mourning. Women and girls deserve to live free from violence. British Columbia deserves a public safety system designed with survivors in mind.

Sep 4, 2025 | Battered Women's Support Services

Across British Columbia, women have been killed in Kelowna, Vancouver, Richmond, Surrey, Abbotsford, and Maple Ridge. In Burnaby, a woman was sexually assaulted in Central Park, a reminder that violence in public spaces persists. In Langley, a woman was severely injured when a substance was thrown on her, burning her body. These events show the range of violence women experience, from femicide to sexual assault to brutal attacks, and they reveal how urgently municipalities must act.

At Battered Women’s Support Services, we know local governments are central to ending this violence. Municipalities oversee the systems where safety is either supported or undermined: housing, transit, parks, lighting, policing oversight, and community programs. They are not bystanders; their decisions directly affect whether survivors live safely.

Our initiative, #DesignedWithSurvivors, reframes gender-based violence as a public safety crisis. The guiding question is simple yet transformative: what would public safety look like if it were designed with survivors in mind? Since May, we have contacted every mayor and council in BC, inviting them to meet with us, learn from survivors, and commit to action. To ensure transparency, we launched a public tracker showing which municipalities have stepped forward, which are preparing to do so, and which remain silent.

The response has been encouraging. We have met with leadership in Surrey, Vancouver, Richmond, Abbotsford, Kelowna, Burnaby, and Maple Ridge—municipalities where women have been killed or where serious violence has occurred. These conversations have focused on concrete steps such as establishing gender-based violence task forces, embedding survivor-centred risk assessment into safety planning, and advancing resolutions for the Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM) convention. Meetings are also scheduled with Langley, Trail, Ucluelet, and Tumbler Ridge. The momentum is growing.

The urgency is undeniable. In Maple Ridge, the disappearance of Jessica Cunningham and the discovery of human remains in her home shocked the community. In Burnaby, the Central Park assault showed that women are still unsafe in public spaces. In Langley, the attack that left a woman with chemical burns highlighted another dimension of this crisis. Residents are not asking for more headlines; they are demanding action.

The lessons from Ontario’s Renfrew County Inquest show what action looks like. In 2015, three women—Carol Culleton, Anastasia Kuzyk, and Nathalie Warmerdam—were murdered on the same day by a man with a known history of violence against them. The inquest that followed in 2022 examined the systemic failures that allowed the killings to occur. The jury issued eighty-six recommendations, including a clear directive that municipalities must integrate intimate partner violence into their community safety and well-being plans.

The inquest also stressed the importance of risk assessment. It called for a common framework to identify risk and lethality in intimate partner violence cases, co-training for justice and community personnel, and the consistent use of survivor-informed risk assessments in bail, plea, and sentencing decisions. These are practical reforms designed to prevent women from being killed after their risks are visible but ignored. Without consistent, survivor-centred risk assessment, tragedies will continue.

Here in British Columbia, Dr. Kim Stanton’s 2025 Independent Systemic Review confirmed the same failures. Her report documented how police, Crown counsel, and courts routinely fail to assess risk in cases of intimate partner violence and sexual assault. Women are being left unprotected because warning signs are disregarded. Stanton’s findings echo the Renfrew Inquest: risk assessment is not bureaucratic procedure, it is a matter of life and death.

When BWSS meets with municipal leaders, we bring these lessons forward. Cities can show leadership by embedding survivor-centred risk assessment into their community safety strategies. That means ensuring local policing contracts and safety plans include evidence-based assessments. It also means creating municipal gender-based violence task forces that unite service providers, justice representatives, and survivor advocates to monitor risks and design prevention strategies. These steps are structural, not symbolic, and they can save lives.

UBCM is the next critical moment. Each year, municipalities across the province debate and adopt resolutions that influence provincial policy. This September, municipalities can demonstrate leadership by adopting survivor-centred motions: declaring intimate partner violence and gender-based violence a public safety epidemic, integrating risk assessment into community safety plans, and establishing gender-based violence task forces. Together, they can send a clear message to the provincial government that local governments will not remain passive in the face of femicide and violence against women.

We are already seeing what change looks like. Municipalities are listening, survivors are being heard, and councils are beginning to act. The momentum we have built in only a few months shows that local governments understand their role in creating safer communities. BWSS is committed to supporting them with policy analysis, survivor expertise, and practical recommendations. Our tracker is not only a record of who has responded, it is a tool for accountability and public engagement.

The message to municipalities is straightforward: the time to act is now. Women and gender-diverse people cannot wait for another inquest or another report to confirm what we already know. Public safety designed with survivors in mind is safer for everyone. Cities that prioritize survivor-centred strategies will be stronger, more inclusive, and more resilient.

The killings in Kelowna, Vancouver, Richmond, Surrey, Abbotsford, and Maple Ridge, together with the sexual assault in Burnaby and the brutal attack in Langley, should never have happened. They must serve as catalysts for systemic change. With survivor-centred planning, consistent risk assessment, and municipal leadership, BC can move from words to action and from silence to accountability. BWSS is proud to lead this campaign and remains committed to working with municipalities, provincial leaders, and communities to end intimate partner violence and femicide.

Aug 26, 2025 | Battered Women's Support Services

Today, gender justice and anti-violence organizations from across British Columbia met with Rechie Valdez, Canada’s Minister for Women and Gender Equality and Secretary of State for Small Business and Tourism.

Organizations representing the north-west and north coast, rural and remote communities, provincial associations, Indigenous and Black women’s organizations, law reform advocates, anti-violence programs, child care advocates, and sexual assault centres came together with a unified message: survivors, girls, women, and gender-diverse people frontline services, and equality movements across BC are speaking with one voice.

The roundtable opened with a territorial welcome from Summer Rain, Manager of the Justice Centre at BWSS, followed by a moment of silence honouring women and girls lost to femicide in BC.

To frame the discussion, participants introduced two powerful visuals: the “Wall of Rollback Receipts” documenting federal cuts and failures, and the “Equality Opportunities Wall – #DesignedWithSurvivors” outlining solutions and pathways forward.

A round-robin of interventions then followed, with organizations from across BC highlighting key themes: sector funding and stability, Indigenous women and MMIWG, rural and northern realities, Black and immigrant women’s leadership, law reform and justice, child care and the care economy, and girls’ safety and leadership.

Together, organizations presented a unified voice through three core asks:

-

Stable, core, multi-year funding for the sector.

-

Shifting investment toward the care economy, housing, and prevention.

-

Independent, survivor- and Indigenous-led accountability for the NAP and MMIWG Calls for Justice.

Minister Valdez was invited to reflect and asked for one clear commitment to carry forward to Cabinet. The meeting closed with a collective affirmation that survivors’ safety is public safety, and a shared commitment to follow up ahead of the Fall 2025 federal budget.

Statement from BC Gender Justice and Anti-Violence Organizations

An Urgent Meeting in an Urgent Time

We thank the Minister for her time and openness to hearing directly from frontline organizations. This meeting was an important opportunity for BC leaders to present evidence, experiences, and solutions rooted in the realities of survivors across our province.

- What we shared was clear: the situation facing women, girls, and gender-diverse people in BC is dire.

- Every 6 days a woman in Canada is killed by her partner.

- BC has some of the highest femicide rates in the country, with recent tragedies still fresh in our communities.

- Resource extraction and man camps continue to put Indigenous women and girls at risk, in direct contradiction to the MMIWG Calls for Justice.

- The National Action Plan on Gender-based Violence has not achieved enough profile and there is not commitment to continue beyond year 5.

- The housing and child care crises traps survivors in unsafe situations and prevents them from building safe futures.

- Digital misogyny and online harms are targeting girls, normalizing violence, and fuelling extremist ideologies.

- And now, an 80% cut to WAGE’s budget threatens to gut the very sector working to hold the line.

- BC organizations highlighted our unique realities:

- The province’s femicide crisis is deepening, with women and girls killed in Abbotsford, Kelowna, Richmond, Surrey, Vancouver and beyond.

- Extractive projects in northern and rural BC make this province a frontline for resource-linked violence against Indigenous women and girls.

- Housing costs and shortages in BC are among the worst in Canada, child care are the highest in Canada, both intensifying the dangers survivors face.

Three Core Asks

Together, we called on Minister Valdez to advance three urgent priorities:

- Stable, core, sufficient multi-year funding for the gender justice and anti-violence sector, ending the cycle of project-based precarity.

- Shifting federal investment toward the care economy, child care, housing, and prevention — recognizing that these are violence prevention measures as essential as policing or infrastructure.

- Independent, Indigenous- and survivor-led accountability for the National Action Plan on Gender-Based Violence and the MMIWG Calls for Justice, ensuring promises do not remain words on paper.

The BC Difference

BC organizations highlighted our unique realities:

- The province’s femicide crisis is deepening, with women and girls killed in Abbotsford, Kelowna, Richmond, Surrey, Vancouver and beyond.

- Extractive projects in northern and rural BC make this province a frontline for resource-linked violence against Indigenous women and girls.

- Housing and child care costs and shortages in BC are among the worst in Canada, intensifying the dangers survivors face.

Our Commitment

Organizations across BC are committed to working with Minister Valdez and WAGE, but we will also hold the federal government accountable. Our work is not optional — equality organizations are the backbone of public safety, economic participation, and democracy in Canada.

Quotes:

“Child care in BC is the most expensive in Canada and there’s only enough licensed child care for 25% of children in our province. Women with children fleeing violence need access to $10aDay child care where educators are valued and fairly compensated.”– Sharon Gregson, Coalition of Child Care Advocates of BC and $10 a Day Child Care

One in three women in B.C. have experienced sexual assault and this is unacceptable. – Laurie Hannah, Westcoast Community Resources Society

“The heaviest consequences are disproportionately carried by racialized and Immigrant women” – Nataizya Mukwavi, Black Women Connect Vancouver and Pacific Immigrant Resources Society

“There can be no meaningful access for justice for women and gender-diverse people without the advocacy and support services provided by our sector. – Shannon Daub, West Coast LEAF

“Women and children cannot survive another era of austerity.” – Jennifer Mackie, Fraser Region Aboriginal Friendship Centre Association

“The creation of safe and affordable housing is a key lever for addressing women’s safety and investments are necessary because the home can be one of the most dangerous places.” – Amy Fitzgerald, BC Society of Transition Houses

“Women, girls and gender diverse folks in the north need and deserve safety.” Lynnelle Halikowski, Prince George Sexual Assault Centre

“Every six days a woman in Canada is killed by her partner. In British Columbia, we are losing women and girls at an alarming rate, yet the federal government has not committed to the National Action Plan on Gender-based Violence past year five. Today, we are telling the Minister clearly: gender equality is not optional. Without safety for women, girls, and gender-diverse people, there is no public safety in this country.” – Angela Marie MacDougall, BWSS Battered Women’s Support Services Association

Attendees

- Amy FitzGerald – BC Society of Transition Houses

- Nataizya Mukwavi – Black Women Connect Vancouver and Pacific Immigrant Resources Society

- Angela Marie MacDougall – BWSS Battered Women’s Support Services

- Sharon Gregson – Coalition of Childcare Advocates of BC $10 a Day Child Care

- Alice Kendall – Downtown Eastside Women’s Centre

- Ninu Kang – Ending Violence Association of BC

- Jennifer Mackie – Fraser Region Aboriginal Friendship Centre Association

- Sue Brown – Justice for Girls

- Lisa Schmidt – ‘Ksan Society

- Lynnell Halikowski – Prince George Sexual Assault Centre

- Shahnaz Rahman – Surrey Women’s Centre

- Laurie Hannah – Westcoast Community Resources Society

- Shannon Daub – West Coast LEAF