Online Abuse and Internet Safety

To quickly exit this website, click the escape key on the top left-hand side of your computer keyboard.

Technology can be an essential resource to access information and a valuable platform to connect with friends, family members, advocates, and service providers for anyone experiencing gender based violence.

Technology can also be used by abusive partners to begin, continue, or escalate abuse, which is why it is important to plan for your safety online.

Internet Safety

Always keep your safety in mind and be sure to clear your browser history of content you wouldn’t want your partner to see, including this website.

To quickly exit this website, click the escape button on the top left-hand side of your computer keyboard.

At the top of each page, BWSS has a “EXIT” button; when you click this link, you will be automatically redirected to a generic Google news page. This is an important safety strategy for you. If you are viewing the BWSS website and you feel that your safety may be compromised you may click this button to immediately leave the BWSS website.

Please note: clicking this button will only re-direct your current browser tab and open a new tab to a generic weather site; it will not remove the BWSS website from your browsing history.

To browse this website safely we recommend using the Google Chrome browser in “Incognito Mode.” When you switch it to incognito browsing, the pages you search and visit will NOT appear in your browser history or search history.

To open an incognito window, start Chrome and click the wrench icon in the top right corner of the screen. Click New Incognito Window and start browsing. Alternatively, press Ctrl + Shift + N to bring up a new incognito window without entering the Chrome settings menu.

If you are browsing this website from a computer in a location where your security may be compromised, please ensure that you clear your browser’s history when you have finished. Common internet browsers have different ways to clear their history.

To clear your recent internet browsing history:

Google Chrome

- Click the Chrome menu on the browser toolbar.

- Select Tools.

- Select Clear browsing data.

- In the dialog that appears, select the “Clear browsing history” checkbox.

- Use the menu at the top to select the amount of data you want to delete.

- Select beginning of time to clear your entire browsing history.

- Click Clear browsing data.

For detailed step by step instructions, click here

Internet Explorer

- Close all running instances of Internet Explorer and all browser windows.

- In Control Panel, click Internet Options.

- Click the General tab, and then click Clear History.

- Click Yes, and then click OK to close the Internet Options dialog box

For detailed step by step instructions, click here.

Mozilla Firefox

- At the top of the Firefox window on the menu bar, click on the Tools menu, and select Clear Recent History

- Click the drop-down menu next to Time range to clear to choose how much of your history Firefox will clear.

- Next, click the arrow next to Details to select exactly what information will be erased.

- Choose Browsing & Download History, Form & Search Bar History, and Cache.

- Finally, click the Clear Now button and the window will close and the items you’ve selected will be cleared.

For detailed step by step instructions, click here.

Apple Safari

- To clear the entire list, choose History -> Clear History.

- To clear individual items from the list, click the open-book icon, click History in the Collections (left) column, and then highlight the items you want to clear and press the Delete key.

- To have the history list automatically cleared, choose Safari -> Preferences, click General, and choose an option from the “Remove history items” menu.

For detailed step by step instructions, click here.

Interactive Safety Planning

What is Online Abuse?

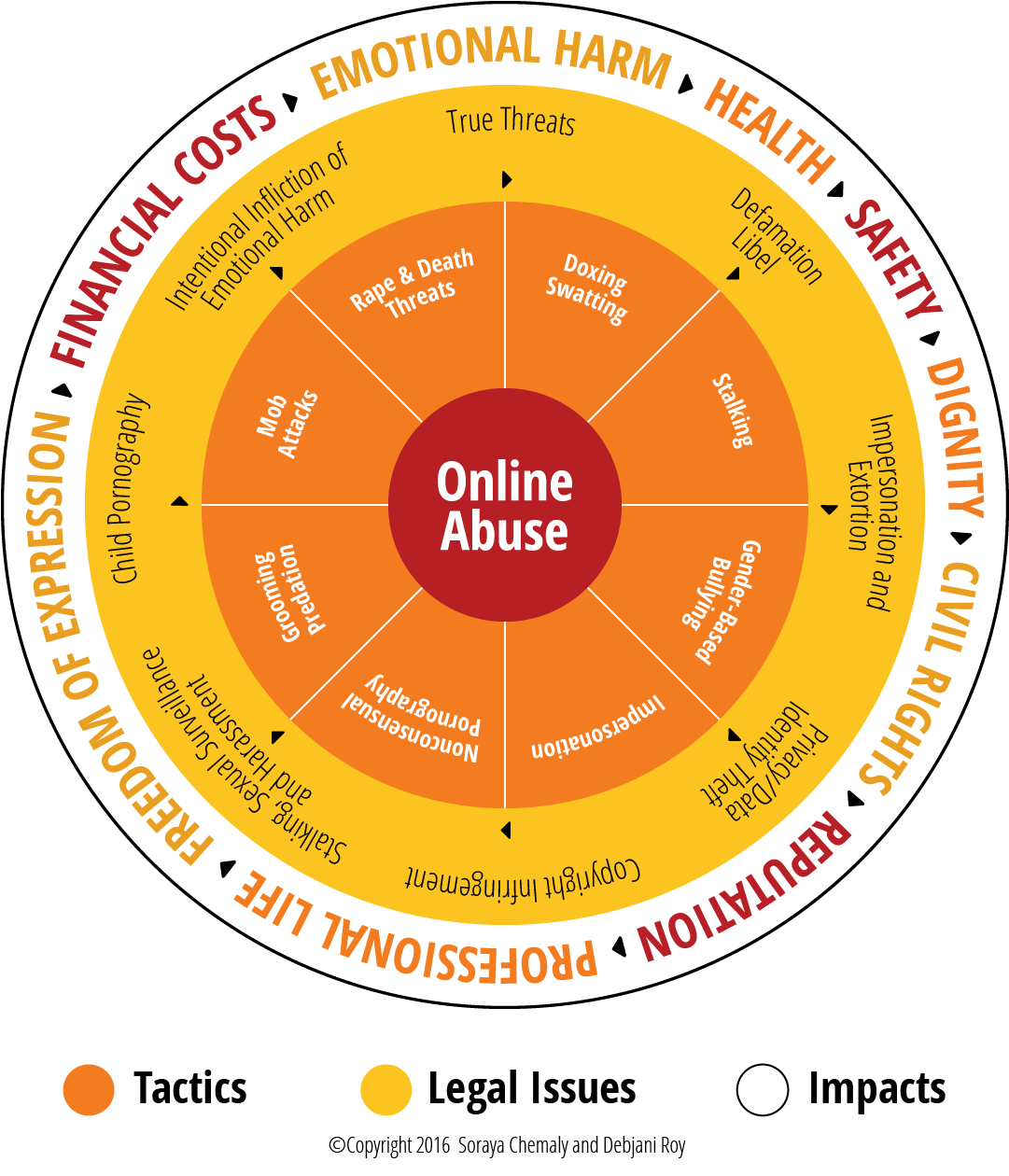

The online harassment of women, sometimes called Cybersexism or cyber misogyny, is specifically gendered abuse targeted at women and girls online.

Online Abuse incorporates sexism, racism, religious prejudice, homophobia and transphobia.

Online abuse includes a diversity of tactics and malicious behaviors ranging from sharing embarrassing or cruel content about a person to impersonation, doxing, stalking and electronic surveillance to the nonconsensual use of photography and violent threats.

The purpose of harassment differs with every incidence, but usually includes wanting to embarrass, humiliate, scare, threaten, silence, extort or, in some instances, encourages mob attacks or malevolent engagements.

Online Abuse Tactics

Tactics are wide ranging from sometimes legal, but harmful, consequential, or in violation of a particular platform’s guidelines and terms of service.

Some online abuse tactics are illegal including but not limited to Child Pornography, Copyright Infringements, Data Theft, Defamation, Extortion, Intentional Infliction of Emotional Harm, Libel, Privacy Infringements, Sexual Harassment, Sexual Surveillance, Stalking and True Threats.

Below are a list of tactics and their definitions that abusers may use online, courtesy of the Women’s Media Center.

Cross platform harassment

Cross-platform harassment is very effective because users are currently unable to report this scope and context of the harassment when they contact platforms, each of which will only consider the harassment happening on their own sites.

Deadnaming

This technique is most commonly used to out members of the LGBTQ2S community who may have changed their birth names for any variety of reasons, including to avoid professional discrimination and physical danger.

DOS

Electronically enabled financial abuse

Flaming

Google Bombing

In 2012, for example, Bettina Wulff, the wife of Germany’s then president, sued Google because the company’s autocomplete search function perpetuated rumors that she was once a prostitute.

Hate Speech

Hate speech usually has specific, discriminatory harms rooted in history and usually employs words, action and the use of images meant to deliberately shame, annoy, scare, embarrass, humiliate, denigrate, or threaten another person. Most legal definitions of harassment take into consideration the intent of the harasser. This, however, fails to translate usefully in the case of cyberharassment, the use of the Internet, electronic and mobile applications for these purposes. In the case of technology enabled harassment and abuse, intent can be difficult to prove and diffuse.

For example, most laws do not currently consider third party communications to be harassing. So, whereas the law understands sending someone a threatening message for the purposes of extortion, it does not understand the non-consensual sharing of sexual images to someone other than the subject of the photograph to be illegal or hateful.

IRL Attacks

IRL trolling can also mean simply trying to instill fear by letting a target know that the abuser knows their address or place of employment.

Rape Videos

Sexual Objectification

Spying and Sexual Surveillance

The minimizing expression, “Peeping Tom,” is particularly insufficient given the impact of the nature, scale and amplification of the Internet on the power of stolen images and recordings to be used in harmful ways.

Sexting/Abusive Sexting

While sexting is often demonized as dangerous, the danger and infraction is actually resident in the violation of privacy and consent that accompanies the sharing of images without the subject’s consent. For example, while teenage boys and girls sext at the same rates, boys are between two and three times more likely to share images that they are sent.

Swatting

Abusers will report a serious threat or emergency, eliciting a law enforcement response that might include the use of weapons and possibility of being killed or hurt.

Trafficking

Social media is used by traffickers to sell people whose photographs they share, without their consent, often including photographs of their abuse of women as an example to others. Seventy-six percent of trafficked persons are girls and women and the Internet is now a major sales platform.

Defamation

Doxing

False accusations of blasphemy

Gender-based Slurs and Harassment

Grooming and Predation

Identity Theft and Online Impersonation

Mob Attacks/CyberMobs

Attacks on public figures like Anita Sarkeesian or Caroline Criado-Perez have been conducted by cybermobs.

Nonconsensual Photography or “Revenge Porn”

The distribution of sexually graphic images without the consent of the subject of the images.

The abuser obtains images or videos in the course of a prior relationship, or hacks into the victim’s computer, social media accounts or phone. Women make up more than 95 percent of reported victims.

It is defined as the non-consensual distribution and publication of intimate photos and videos.

Retaliation Against Supporters of Victims

Shock and Grief Trolling

Stalking and Stalking by Proxy

Slut-Shaming

Threats

Unsolicited Pornography

For example, editors at Jezebel reported that an individual or individuals were posting gifs of violent pornography in the comments and discussion section of stories daily. Writers at Jezebel, almost all women, were required to review comments sections daily.

Women politicians, writers, athletes, celebrities and more have their photographs electronically manipulated for the purposes of creating non consensual pornography and of degrading them publicly.

For victims and survivors who want support, we are here for you.

You are not alone and you have options. Our Safety Changes Everything advocates are available to discuss your situation and help create a personalized safety plan that’s right for you.

Planning for safety in different online spaces

Planning for safety can be one way women can take back power in abusive relationships.

Here are some more tips and suggestions on how to be safe online.

Cell Phone Safety

A cell phone used for harassment is a common tool of power and control.

This might include:

- Constantly texting all day long

- Expecting an immediate reply and becoming abusive if you are unable to reply

- Calling you repeatedly from known or unknown numbers

There are cybersecurity strategies that can help you gain more safety.

Most strategies depend on having a smartphone; if you have a regular cell-phone, you will have fewer technical options available, although there will be fewer means of tech-based harassment.

- Blocking a phone-number is one way to cut-off contact from an abusive partner/ex-partner. Unfortunately, for many women this is not always an available solution. For example you may need your partner's number for communicating about your children –or they may change their number or use a different phone number that isn’t blocked.

- Disabling notifications lets you communicate when you feel safe to do so, but also at the expense of instant communication with friends and family. You may need to disable and re-enable notifications throughout the day.

- Some apps, like Messages in iOS (IPhones), can filter unknown phone-numbers into a separate list.

- Disable the read-receipts (the messages that say when someone read your text) means your abusive male partner won't know when you're using your cell phone.

- Turning off location-sharing will hide your physical whereabouts.

- Deleting conversation history can be comforting if you find yourself repeatedly reading old abusive conversations (though you should preserve this history if you need evidence for legal reasons).

- Use alternative texting apps–you can use one specific app if you need to communicate with your partner/ex-partner and that way you can disable notification specifically from that app.

- Consider purchasing a pay-as-you-go phone and keep it in a safe place for private calls.

- Use a password on your phone and update it regularly.

Look into what your phone and your phones apps offer and customize them to what you need. No setting changes have to be permanent and you can always change them when you need to.

Changing Your Phone Number

Changing your number is choice based on the intensity of your partner's harassment, the viability of changing your contact information amongst your social and business networks, and your financial resources.

- Create a back-up of any important photos and conversations that you want to preserve, especially any evidence of abuse.

- Make a note of any online accounts that are connected to your phone number, like social media or banking accounts—sometimes your login information is tied to a cell phone number, so you should update these accounts with your new number if you want to.

- Find out if any of your accounts display your phone number. Profiles, like those on Facebook or LinkedIn, might reveal this data without your knowledge. Then update your settings so that your new phone number will not be visible to the public.

- Once you've changed your phone number, make a point not to give that number to any website unless absolutely necessary.

- Don't hesitate to lie about your phone number, as well as other personal information online. Just because a website requires this data, it doesn't mean you have to compromise your safety. Create a fake number, address, or even a fake name.

GPS Tracking in Cellphones

Your cellphone reveals your physical location at every given moment. GPS, which means "Global Positioning System", determines where your phone is in real-time based on satellites. This isn’t internet based but rather there's a chip in your phone that receives and processes the satellite signals.

Your location can be tracked through apps that use Location Services. Disable Location Services for any app that may compromise your safety. An abusive male partner may secretly download apps on your phone to keep track on where you are, so if you see any unfamiliar apps, delete them right away.

If you are concerned that your partner may be secretly monitoring your phone, consider taking it into a cell phone service center to check for any spyware that may be downloaded.

My partner is monitoring my computer or cell phone activity.

Is your partner monitoring you? Here are some red flags to notice.

- He frequently asks to see your computer or cell phone, or takes it.

- He demands passwords to your computer or cell phone.

- He wants login information for your email, banking, shopping, or social media accounts.

- He is known to be "good with computers" and handles your computer tasks.

- He gives you devices that he’s set-up for you.

- He spends a significant amount of time on his computer and is unusually secretive about it.

- He makes vague references to activities or conversations they were not present for.

- He gets unexpectedly angry towards a person you've recently communicated with.

- He threatens to reveal embarrassing information about you.

Email Safety

An abusive partner is likely to know this and may have access to your email account without your knowledge. To be safe, open an account your partner doesn’t know about on a safe computer and use that email for safety planning and sensitive communications.

Use several different methods of communication when contacting people so that you’ll know if they tried to reach you elsewhere, and keep your monitored account active with non-critical emails in order to maintain appearances.

Encrypted email services can offer an extra layer of security.

Social Media Safety

There is so much gender based violence that can be found on social media. And abusive male partner will be quick to exploit this this vulnerability, either directly harassing you through various online platforms, or enlisting hate communities to assist in the abuse and harassment. Making your profile private: choosing to be private or public makes you no more deserving of harassment.

Tips on what to do when receiving abuse or harassment on social media:

- One option is to report the abuser through the platform itself.

- Abusive messages that threaten violence are criminal. If you think these threats are an imminent danger, you should contact the BWSS Crisis line, friends or family that can provide safe shelter, or, if you feel safe doing so, the police.

- Collect evidence of the threats –these can be helpful in demonstrating danger to the legal systems, and police.

- While the abusive partner can delete proof of their harassment, you can take screenshots for your personal records, or report the messages to the social media platform so they have a record.

He might use social media by getting friends or family to contact you about your relationship, making you feel pressured or ganged up on. He might monitor your friend's activity on social to gain information about your personal life if you appear on their account. He might post harassing and abusive messages or photos about you, to embarrass you in front of your community.

You can resist social network exploitation through mindfulness and self-care.

- Check your friend or follower list of people who you don't know, or aren't very close with—if you ran into them on the street, would you want to talk to them? If not, delete them.

- When your friends post something about you, in photos or otherwise, politely ask them to withhold that information out of respect for your privacy. It's especially important to discourage "tagging" in photos or posts, which frequently reveal your physical location at a specific time.

- Don't hesitate to block or unfriend people who are contacting you in a way that causes stress, discomfort, or harm: you are not obliged to talk to anyone who makes you feel that way.

- Comment sections are especially cruel, where many people are thoughtless and angry—it's okay to ignore them.

- If your partner is publicly attacking you, report them to the social media platform for harassment.

- You can also take a social media hiatus to reduce stress.

Technology enabled location stalking

It's never been easier to track your daily movements.

GPS technologies are built-into our phones, available for any app that wants to share your location. Photos are embedded with information identifying when and where the photo was taken. Social media posts from your friends reveal where you are and where you are going.

AirTags can be dangerous when stalkers and abusers hide it on a victim, here's how you can protect yourself.

The Compass Card used on Transit compromise women’s safety because it can be used to track the exact time and location a woman uses transit.

It's frightening to know that your partner or ex-partner can track you and important to know that this is stalking. Stalking is illegal and if you are comfortable you can connect with our crisis line for more support or the police.

Changing Passwords

If you think your partner is reading your texts, watching your emails, looking at your photos, or using your cell phone, you can change your passwords to lock them out. Changing your passwords depends on your safety levels. Don't change your passwords if there's a risk of him retaliating. You may not know whether he has your passwords—try changing one password and wait a few days to see if he reacts. If they don't react, try changing another password and repeat the process.

Fingerprint passwords are being used more and more for phones and laptops. While this might seem like a safe way to protect your privacy, your partner could simply swipe your finger while you're asleep or intoxicated, or physically force you to unlock a device.

If you're separated from your partner, change all of your important passwords just to be safe. One option is to use the use a Password Manager. A password manager generates and stores passwords for you, so you don't have to remember them. This makes it impossible for your partner to guess your password or hack into your account. You can also use the Two-Step Verification defense strategy. When you login to a website, you will need a number generated by your phone or received in a text. Even if your partner has your password, they would still need your cell phone to access your website.

Create Back-up Accounts

- Emails –create a forwarding address so every incoming email is sent to an additional email address that your partner doesn't have access to.

- Texts –enable text-forwarding, where your texts are saved on another device: possibly a friend or family member's phone.

- Create secret accounts –create an alternative account your partner doesn't know about. When you register online, use a totally new password, email address, and login name and only use private browsing when on the secret account.

Protecting your apps

- "Short-lived" apps like Snapchat may seem private, but it's very easy for your partner to take screenshots or install software to record snaps. Be aware of app permissions: if there's an app that has unwanted access to your content, either delete the content, or disable permissions for the app.

- Beware of apps that are location-specific like delivery and ride-sharing services.

- Reduce risk by choosing apps that do not back-up to the cloud, do not share across devices, and require a password.

- It's likely that your text messages, photos, and videos are automatically backed-up in the cloud. Deleting them on your device doesn't guarantee that they are deleted in the cloud. When creating sexual content, try to use apps that don't back-up to the cloud, or have back-ups disabled. Securing your cloud with a strong password will reduce the risk of your cloud being hacked.

- Two-Step Verification offers even more security.

Is your personal information being shared online?

Posting your information online is also a common tactic that is used.

This includes sharing phone numbers, addresses, names of family members, embarrassing private information, intimate photographs or texts, and other pieces of personal data can be shared on social media, email, and websites.

Is your partner sharing images without consent?

If you find your sexual content being shared on a website, first collect evidence. Sharing pornography non-consensually violates the law in Canada, so evidence is crucial if you decide to pursue legal action. Then, contact the website about taking down the content.

Is your partner impersonating you online?

This is done through the creation of fake social media accounts, such as a Facebook profile or a Twitter account. If the platform has the option, report the account as an impersonation and/or as harassment. Having friends/family report the account may increase the possibility of a response from the platform.

I'm Afraid of My Sexual Content Being Hacked.

Even if you delete the content in one location, it could still survive elsewhere. To protect your sexual content, be aware of where the data lives, choose apps that offer control over your media, and secure your devices and accounts. It's okay to skip the following strategies when it doesn't feel safe for you.

Answers to Frequently Asked Questions

The UN estimates that 95% of aggressive behaviour, harassment, and abusive language in online spaces are aimed at women and come from current or former male partners. This behaviour is used to control, intimate and isolate women and girls. Below are some answers to frequently asked questions, courtesy of the Women’s Media Centre.

Isn’t online abuse “just bullying”?

While this definition provides an excellent framework, definitions can and do differ greatly and don’t necessarily align with academic and research definitions. Legal definitions of bullying and harassment vary by jurisdiction and the term bullying most frequently involves the targeting of children and teens. For example, only 16 US states define bullying as encompassing only behaviors that are intentional; seven states define it to include only behaviors that a ‘reasonable person’ thinks would harm another person.” Only four states take into account power imbalances.

Why focus on women, if everyone is harassed and whose experiences can be radically different?

When men face online harassment and abuse, it is first and foremost designed to embarrass or shame them. When women are targeted, the abuse is more likely to be gendered, sustained, sexualized and linked to off-line violence.

Women, the majority of the targets of some of the most severe forms of online assault – rape videos, extortion, doxing with the intent to harm – experience abuse in multi-dimensional ways and to greater effect. They are the vast majority of the victims of nonconsensual pornography, stalking, electronic abuse and other forms of electronically-enhanced violence.

In addition, women report higher rates of finding online abuse stressful. This is not because they “can’t stand the heat,” as is frequently suggested, but because the abuse online exists simultaneously with three facts:

- Women have to be hyper-vigilant in daily life. A double digit safety gap offline has an online corollary. Women are more likely to experience more gendered and consequential abuse. They are more frequently harassed, online and off, for sustained periods of times, in sexual ways and in ways that incorporate stalking and manipulation. They are more likely to be pornographically objectified and subjected to reputation damaging public shaming. Sexual slurs toward women evoke the threat of real-life sexual violence; they are also perceived as intended to “put a woman in her place” and tell her that her opinion is worthless because she is a woman.

- The online abuse women experience is intersectional. Women all over the world are experiencing misogyny online, but rarely is it experienced along only one dimension. Women who are targeted because of their race, ethnicity, sexuality or disability face abuse on multiple fronts and report higher rates of emotional and psychological harm. Sometimes, sexism is married to race, others to caste, others to sexuality – the overlap has a compounding effect. A lesbian woman experiences homophobia and sexism. A black woman, racism and sexism. A Moslem or Jewish woman, religious hatred and sexism.

- Globally, women still face sexist, patriarchal (power-over domination of all kinds) constraints that compound the negative effects of online harassment . There are preexisting, offline limitations on our ability to work, go to school, earn money, be politically active and shape culture. Limitations that, for the most part, men do not face. When girls and women are harassed online, that harassment taps into these restrictions and the potential damage is amplified. Girls and women are more likely to face bullying, harassment, censorship and abuse that reflect preexisting, and still enforced, sexist double standards and the disproportionate effect of honor culture norms. Many of the most commonly employed tactics rely on preexisting double standards regarding sexual behavior. Harassers, for example, count on women being judged for their sexual behavior and shamed and penalized because of it.

- The harassment men experience also lacks broader, resonant symbolism. Women are more frequently targeted with gendered slurs and pornographic photo manipulation because the objectification and dehumanization of women is central to normalizing violence against us. Philosophers Martha Nussbaum and Ray Langdon describe in detail how this works: women are thought of and portrayed as things for the use of others. Interchangeable; violable; silent and lacking in agency. Much of the harassment that women are subjected to online reflects these uses of objectification.

Aren’t anonymity and stranger danger the problem? And, if we get rid of it, won’t online abuse go away?

Most women are harassed online by people they know: school peers, acquaintances, intimate partners, former intimate partners, employers and, in some countries, religious and political authorities. Many of these people do use anonymity to perpetrate abuse, but anonymity itself isn’t the problem.

Anonymity is often a lifeline for people online, an essential dimension of privacy and freedom from violence. There are many movements, globally, such as the #Nameless Coalition, encouraging platforms to create more nuanced and flexible approaches to the problems presented by anti-anonymity policies.

Online abuse isn’t really violent, right? Not compared to offline violence?

Harassment online is a very strong thread in an already densely woven fabric of socially acceptable and institutionalized resistance to women’s full participation in the world.

A teenage girl in Pakistan might not only be harassed online, but might find that her life is at risk if her family finds out about her online life or because a conservative member of her community non-consensually shared a photograph of her on Facebook.

A woman in Texas whose ex-husband nonconsensually shares naked pictures of her, might legally be fired by her conservative employer.

A girl in Canada might kill herself after a video of her rape is shared electronically, and her classmates slut-shame her, literally to death.

A writer might have to cancel speaking opportunities because of threats made on an open-carry campus.

A trafficked 10-year old in a country where child marriage is acceptable might be terrorized when her trafficker tweets a picture of himself drowning her best friend in a toilet, just to prove he can.

A woman’s small business might collapse after an online mob actively decides to flood Yelp reviews with defamatory comments.

But, aren’t men harassed, too?

Don’t Women Harass Online As Well?

Aren’t only women celebrities and writers being harassed? Aren’t they public figures and harassment goes with the territory?

What are the costs of online abuse?

Online abuse exacts many costs that are routinely minimized. Online harassment can be a steep tax on women’s freedom of speech, civic life, and democracy. It can and does inhibit their economic and educational opportunities. For women, harassment frequently perpetuates harmful stereotypes, is sexually objectifying and relies on the threat of violence to be effective.

Some of the most commonly reported costs of online abuse reported by victims and survivors are:

Personal costs

- Emotional and psychological distress and health problems related to anxiety, depression, anger, post-traumatic stress and hypervigilance

- Concerns about physical safety

- Concerns about the safety of immediate family

- Concerns about employers and family members finding out or being affected by harassment

- Incurring financial costs of trying to avoid or offset harassment and abuse

- Physical assault

- Privacy violations

The seamlessness of online and offline violence means that real world safety gaps are made even more pronounced. Perpetrators of intimate partner violence, stalkers and anonymous harassers all rely on pre-existing violence, and societal tolerance of that violence, to leverage new technologies. According to research conducted by the National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV), 89 % of domestic violence programs report that victims experience intimidation and threats by abusers via technology, including through cell phones, texts, and email.” Intimate partners create impersonator content online, sometimes with brutal results. While media narratives often focus on stranger abuse and harassment, the fact is that the most sustained and destructive examples of abuse online, like offline, are most likely to be perpetrated by people known to victims. While this is true worldwide, there are also unique physical risks in countries where free speech norms and gender imbalances differ from those in the US. For example, in countries with highly punitive laws against blasphemy and/or where women are discouraged from engaging in public expression and political life, online abuse is enabled.

Professional costs

Harassment frequently involves harm to professional life and impairs people’s ability to pursue economic opportunities. Targets of harassment frequently worry about damage to their reputations and professional lives, their ability to find work and loss of employment. Women who are targeted, for example, might be bombarded with bad reviews for their place of business or their work products. Search engines might be maliciously optimized to highlight unflattering, inaccurate information.

Harassment makes women’s participation in male dominated fields or quickly evolving new markets difficult. Hostility towards girls and women in new and expanding markets is often particularly pronounced. Misogyny and sexism expressed profusely, for example, in gaming or sports, inhibit women’s ability to fully participate and be taken seriously when they do. Harassment reduces opportunities to engage as equals, be seen as authoritative or compete with for employment and education opportunities.

Civil and Human Rights

Danielle Citron and Mary Anne Franks argue that online abuse is, first and foremost, a civil rights issue, not only for women but for other historically discriminated against and marginalized groups. “Civil rights laws,” writes Citron in her book, Hate Crimes in Cyber Space, should “redress and punish harms that traditional remedies do not: the denial of one’s equal right to pursue life’s important opportunities due to membership in a historically subordinated group.”

According to global studies conducted by Take Back the Tech one in five women report that “the internet is inappropriate” for them. Fear of online violence, shaming, spying and tracking are significant impediments to women’s adoption and use of internet and mobile technologies. As a result, they are effectively, systemically restrained from participating as equals in civic and economic growth opportunities.

Harassment substantively constrains free speech. Many free speech absolutists think of safety and free speech as being in opposition to one another, as in, if we make changes to ensure people’s safety online we will necessarily squelch free speech. This equation fails to consider that for marginalized and non-dominant groups safety and free speech go hand-in-hand, and that the steps necessary to ensure the safety of people online rarely require new ways of censoring speech, but rely on the proper and fair execution of existing laws and policies.

Journalists and Media Marginalization

Hostility to women’s public engagement is hardly a new phenomenon and the experiences of women journalists and writers attests to its persistence today. An analysis of online harassment in Twitter conducted in 2014, for example, revealed that women journalists and writers are among the most targeted for online abuse. Research shows that women silence themselves, opt out of doing certain work, avoid certain topics, are fearful and restrict their level of public engagement.