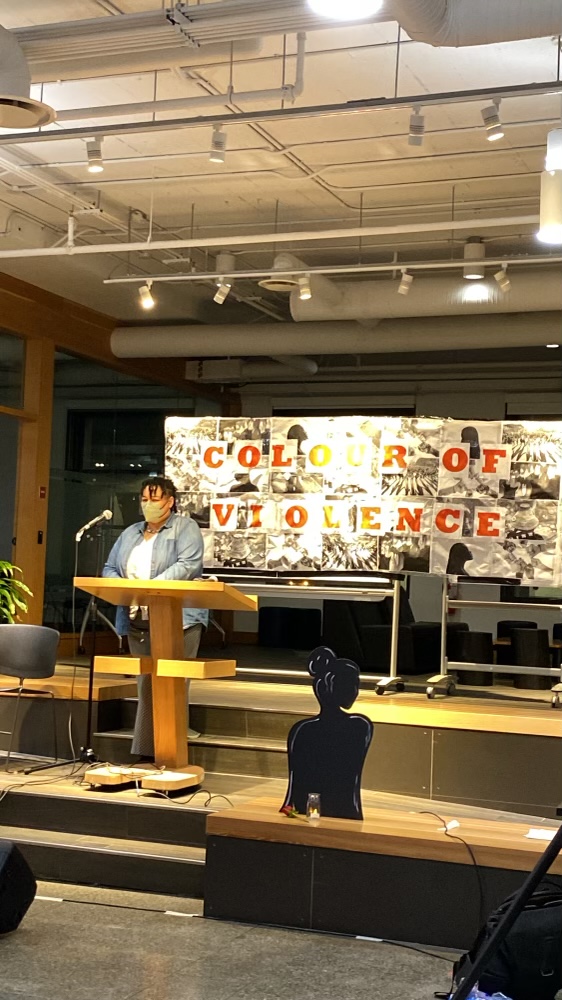

Our “Colour of Violence: Race, Gender & Anti-Violence Services” report and accompanying toolkit explores the extent to which gender and race influence system-based responses to gender-based violence. We conducted surveys with 105 racialized survivors as well as focus groups with dozens of anti-violence workers of colour to better understand the barriers to safety for racialized survivors across the province. We are deeply grateful to all the participants who brilliantly and courageously shared their time and insights with us. Based in anti-oppressive, anti-racist, decolonial, and feminist principles, our report actively positions these participants at the very center of our anti-violence work.

Our “Colour of Violence: Race, Gender & Anti-Violence Services” report is motivated by the urgency of our moment. Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, violence against women and girls, particularly domestic violence, has intensified and become a shadow pandemic. Crisis lines, including BWSS’s crisis line, and violence against women shelters in Canada are reporting increases of 20 to 50 percent, while national rates of reported femicide are also increasing. From Vancouver to Winnipeg, the horrific murders of Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit people is part of the ongoing gendered colonial genocide. Still, Canada has extreme difficulty recognizing how deep and profound racism is, and how racism is instrumental in compounding the impact of gendered violence. As one project participant told us, “Understand that racism exists, and survivors experience it.”

Our “Colour of Violence: Race, Gender & Anti-Violence Services” report examines the specific and unique intersections of race and gender for Black, Indigenous, newcomer immigrant/refugee, racialized survivors in B.C. It also explores and raises awareness on the experiences of Indigenous, Black, newcomer immigrant/refugee, and racialized survivors accessing formal, institutional responses to gender-based violence. Through this work we challenge the homogenization of “women of colour” and highlight the specific experiences of Black, Indigenous, and newcomer immigrant/refugee survivors, recognizing that gender-based violence is inseparable from the violence of systemic racism, settler-colonialism, anti-Blackness, and migrant exclusion. The goal of the report is thus twofold: to shift our collective analysis of gender-based violence, and to offer concrete anti-racist and intersectional best practices in developing anti-violence interventions.

“We must destroy the myth of the perfect victim, one that has allowed institutions, including the media, education, healthcare, and the courts to maintain that one-size-fits-all model for addressing gender-based violence.” – Project participant

Gender intersects with colonization, race, age, ability, sexual orientation, class, religion, immigration status, and many other factors that all influence how people experience gender-based violence, while simultaneously impacting the kinds of structural supports available to survivors. Despite this, many mainstream conceptions of gender-based violence reproduce a “one size fits all” approach that centers white, middle class, cisgendered women victimhood. The Native Women’s Association of Canada points out how “mainstream gender-based analysis fails to meaningfully address the social, political, and cultural realities of Indigenous women. Culturally relevant gender-based analysis considers the historical and current issues faced by Indigenous women, including the impacts that colonization and intergenerational trauma have caused.”

A lack of disaggregated data magnifies these historical and social barriers. All aspects of systemic, institutional, and governmental responses to gender-based violence tend to default to frameworks that are “race-neutral,” and Indigenous, Black, newcomer immigrant/refugee, and racialized survivors are almost entirely excluded. A “race-neutral” approach is not neutral at all; rather, such an approach takes the shape of centring the experiences of white survivors. This “one size fits all” approach reinforces a white supremacist status-quo.

We, at BWSS, have consistently noted “[O]veremphasizing a criminal justice response and largely ignoring social structures that contribute to violence against women in relationships can strengthen the social/structural underpinnings of oppression. The model of intimate partner violence service provision, which has largely been developed from a white, able-bodied, heterosexual, middle-class woman’s perspective, is encouraged to become more inclusive by adding multicultural components. But simply adding inclusive components does not necessarily shift the perspective that anti-violence service provision was developed from.”

What We Heard

Overall, our findings indicate systemic challenges of access to justice and safety for Indigenous, Black, newcomer immigrant/refugee, and racialized survivors who experience gender-based violence in B.C. Some of the key findings of “Colour of Violence: Race, Gender & Anti-Violence Services” include:

- Racialized survivors are subject to higher probabilities of gender-based violence.

It is well documented that Indigenous women and girls are twelve times more likely to be murdered or missing than any other woman in Canada, and sixteen times more likely to be murdered or missing than white women in Canada. Sexual assault self-reported by Indigenous women is nearly triple that of non-Indigenous women, and Indigenous women are also more likely to face more violent, injurious, and sustained abuse. Similarly, the prevalence of intimate partner violence among Black women is disproportionately high (42 percent) when compared to the total visible minority population (29 percent).

- Racialized survivors face structural barriers in accessing safety and support from gender-based violence.

An alarming 78 percent of racialized survivors whom we surveyed said they felt never comfortable, almost never comfortable, or only sometimes comfortable contacting anti-violence services after experiencing gender-based violence. Only a minority of survey respondents received services that were culturally relevant, multilingual, attentive to the intersection of gender-based violence with race/ racism, and by a worker who was themselves racialized. We heard from one participant about “Stereotypes about who I should be as a woman coming from the Middle East.”

When asked why they did not feel comfortable contacting anti-violence services after experiencing gender-based violence:

- 32 percent said they did not feel comfortable or safe with someone who did not understand their racial and cultural background. For example, one participant remarked “There are very few Black anti-violence support workers in my city, so it is hard to get culturally relevant support.”

- 31 percent said they were afraid of their abuser and retaliation by the abuser or the abusers’ family and/or friends.

- 30 percent said they were worried about government systems being contacted, such as police, immigration enforcement, involuntary mental health services, and child services.

Racialized survivors reported that the police were the least helpful anti-violence response system, while a majority of survey respondents said they relied on and found their informal network of friends and family to be the most helpful.

- Indigenous, Black, and newcomer immigrant/refugee survivors face particularly heightened barriers.

All racialized survivors in our project reported lack of access to culturally safe services; mistrust of the legal system and other state systems; and being minimized or disbelieved. However, Indigenous, Black, and newcomer immigrant/refugee survivors reported particularly heightened barriers to justice, including often being criminalized for reporting violence, having their children apprehended, or facing deportation. As one project participant told us: “It felt like being prosecuted all over again; if the police were contacted, your situation was reported to child protection services.”

Indigenous survivors were more likely not to contact services due to anti-Indigenous racism and fear that the police, criminal legal system, or child services would get involved. Black survivors reported the least trust in police to keep them safe and reported lack of access to culturally relevant support services. Newcomer immigrant/refugee survivors reported the greatest barriers to linguistic and culturally relevant services and expressed fears of contacting services due to their immigration status.

“[I] am a permanent resident and a drug user so at risk of criminalization and potential ejection from the state. I am a former sex worker so constantly worried about opening myself up to unnecessary scrutiny.” – Project participant

We hope that our “Colour of Violence: Race, Gender & Anti-Violence Services” report provides key insights, best practices, and the momentum necessary for social change. We hope that you join us in honoring the strength of all those who shared their insights and experiences with us and join us in amplifying their truth-telling toward action. Ensuring access to meaningful and holistic safety and justice for Indigenous, Black, newcomer immigrant/refugee, and racialized survivors must become a pressing priority for us all.