Remarks by Angela Marie MacDougall

Executive Director, Battered Women’s Support Services

Victoria Courthouse Press Conference – attended virtually

Thank you.

My name is Angela Marie MacDougall, and I’m the Executive Director of Battered Women’s Support Services in British Columbia.

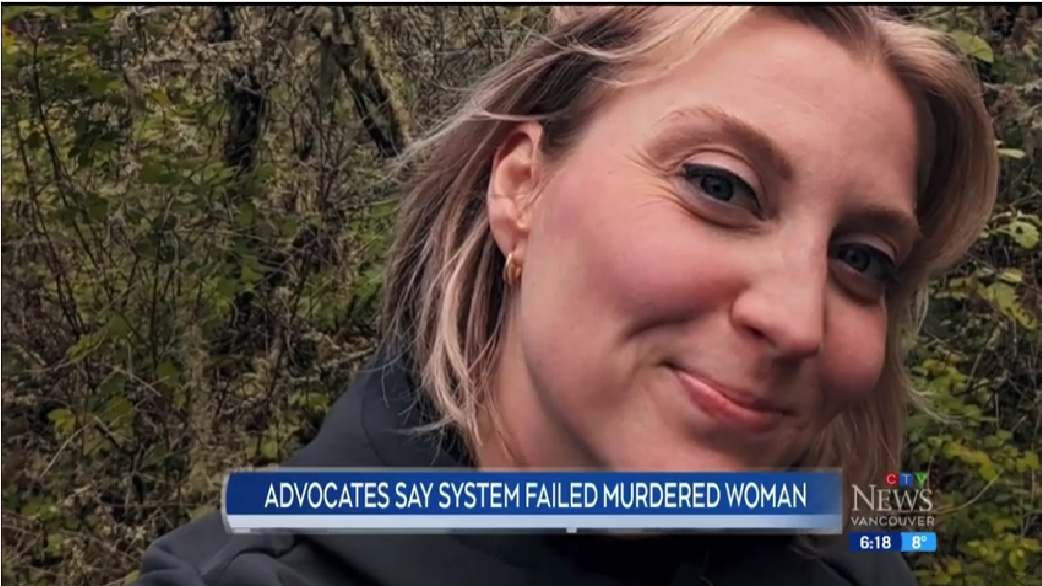

I’m here today not only because of the killing of Laura Gover, but because what happened here fits a pattern that all levels of government already know, already recognize, and have already said they intend to address.

And yet women keep being killed.

It was in the1990’s that anti-violence organizations began pressing governments and more recently with urgency after nearly forty-five women have been killed since August 2024. These deaths did not happen in ignorance. They happened during a period when all levels of government were acknowledging risk, commissioning reports, and promising reform.

That matters.

Because it tells us this is not about a lack of evidence.

It is not about a lack of tools.

It is about a lack of ownership.

What we are seeing is systemic, and it sits at the intersection of police practice, Crown decision-making, judicial discretion, and a deep structural divide between criminal law and family law.

Many women leave abusive relationships and never involve the criminal legal system at all. If they have children with their abusive partner, they are forced to go to family law. They seek protection orders through the family law system. And they do exactly what they are told to do to keep themselves and their children safe.

And they reasonably believe that once the state is involved, risk will be reduced – they are optimistic.

But risk lives in the space between systems.

And no one owns that space.

Police can say they did not meet a threshold.

Crown counsel can say the file was insufficient.

Judges can say they ruled on what was before them.

The family law system can say it is acting in the best interest of the children

And the woman is left unprotected.

When institutions are organized this way, responsibility is endlessly deferred while danger escalates.

The Attorney General has said that risk assessment is a priority.

The Stanton report laid out the failures clearly.

Articulating an intention to do something but there are no timelines.

No public benchmarks.

No implementation deadlines.

Without timelines, governments can sit on intentions indefinitely.

That is not neutral. That is a choice.

Risk assessment in theory without obligation becomes performative.

Commitments without deadlines become delay.

And women die in that space. Women die in that space. This is the space where women die.

We are not here simply to name failure. We are here to be clear about what prevention actually requires.

Our Five Asks of all levels of government are not radical. They are the minimum conditions for safety.

We are calling for mandatory, standardized risk assessment across police, Crown, courts, child protection, and family law, so danger is identified early and acted on consistently.

We are calling for municipal gender-based violence task forces in every community, because local governments must treat this as a core public safety responsibility, not a social service issue to be downloaded to the victim and uploaded to provincial or federal governments.

We are calling for stabilized core funding for frontline anti-violence services, a minimum 15% bump in emergency funding to meet this current crisis so victims and survivors can access crisis response, legal advocacy, housing support, and counselling without delays, waitlists, or gaps.

We are calling for a long-term prevention campaigns, so the public understands coercive control, strangulation, stalking, digital violence, and other indicators of escalating risk.

And we are calling for a dedicated gender-based violence lead within Public Safety and the Attorney General’s offices, with authority to coordinate system change, ensure oversight, and monitor implementation across ministries.

None of these work in isolation. Together, they create prevention.

Accountability also matters after death.

We are calling for mandatory coroner’s inquests in femicide cases where a protection order or peace bond was sought or granted. Not to assign individual blame, but to expose systemic gaps, missed interventions, and institutional failure so they cannot be ignored or repeated.

Governments often point to bail reform as evidence of action.

But tools only matter if they are used.

In October 2025 in Kelowna three months after the horrific femicide of Bailey McCourt, in a different case, an accused had his bail revoked only after a judge conducted a risk assessment. That tells us something important. The problem is not the absence of tools. The problem is the failure to apply them consistently.

Governments know how to own complex, high-risk infrastructure when they choose to.

Building new Highways come with timelines – Pipelines come with timelines.

They come with oversight.

They come with leadership and consequences for failure.

Women’s safety does not.

Gender-based violence and in particular intimate partner violence continues to be treated as a private issue when it must be governed as social public safety infrastructure.

Femicide is predictable.

Femicide is preventable.

What is missing is political ownership – from all levels of government.

Women are being killed in the space between systems that refuse to own the outcome.

And that is what must change.

Thank you.